The underwater communication and navigation system is equipped with the world’s first “Diver Physiological Monitoring” feature, which breakthroughly resolves the technical challenge of transmitting physiological data in real time underwater. This enables surface command personnel to continuously monitor the diver’s key physiological parameters.

At the core of this feature is the Diver Physiological Monitoring Belt, which accurately collects and synchronizes critical indicators such as heart rate and blood oxygen saturation. It does so without compromising the sealing or proper wear of either wet suits or dry suits, ensuring real-time data transmission while maintaining both the safety and comfort of diving operations.

Divers wear the “Diver Physiological Monitoring Belt” before entering the water

Before a dive mission begins, the diver simply wears the Diver Physiological Monitoring Belt on the upper arm—snug against the skin but not tight, so as not to impede blood circulation. Once powered on, the device pairs wirelessly with the system via Bluetooth.

Made from highly elastic material, the belt adapts to changes in underwater pressure, ensuring stable data collection even in deep-water or prolonged dives. The collected data is transmitted in real time through the acoustic communication link to both the diver’s Dive Navigation Computer and the Topside Control Center, providing a dual-layer safety guarantee of “self-monitoring by the diver + surface supervision.”

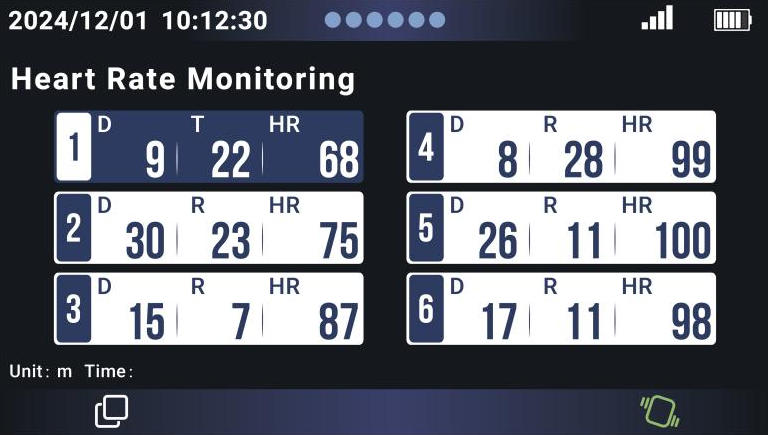

The system can wirelessly collect and transmit divers’ heart rate data in real time. Divers can view their own heart rate trends through a visual interface on the dive navigation computer, providing an intuitive understanding of their physiological state. Meanwhile, surface command personnel can monitor the heart rate status of all online divers via the surface control center, achieving comprehensive situational awareness.

If a diver’s heart rate exceeds the preset safety range—due to stress, fatigue, danger, or panic—the diver’s device and surface control center simultaneously trigger vibration and audible-visual alarms. Command personnel can immediately intervene via the underwater communication system to inquire about the situation and provide guidance, enabling rapid response and risk mitigation.

The system continuously monitors and transmits divers’ blood oxygen saturation (SpO₂) levels in real time, a key parameter for assessing physical condition and respiratory function. Divers can clearly view their own blood oxygen readings on the dive navigation computer, while surface command personnel can monitor the entire team’s SpO₂ status, achieving full situational awareness.

If a diver’s blood oxygen level drops below the safe threshold—due to irregular breathing, minor equipment leakage, or other causes—the terminal displays a red warning and activates a buzzer alert. Surface command personnel or the diver themselves can immediately adjust breathing patterns or initiate an emergency ascent, effectively preventing risks such as hypoxia, loss of consciousness, or decompression sickness.

The enclosed and complex nature of underwater environments has long made physiological monitoring lagging or reactive. Traditional methods rely on divers surfacing to measure vital signs, or on subjective self-reporting. In the event of sudden issues—such as rapid heart rate drops or critically low blood oxygen—surface personnel often cannot detect problems in time, frequently missing the optimal window for rescue.

For instance, if a diver is struck by an underwater current, excessive stress may cause their heart rate to spike to 160 beats per minute. Without real-time monitoring, the diver could overexert themselves, placing excessive strain on the heart.

Similarly, if a wetsuit or drysuit develops minor leakage, the resulting drop in body temperature could gradually reduce blood oxygen levels. If this goes undetected, it may lead to confusion or impaired consciousness, increasing the risk of losing contact with the surface team.

The real-time diver physiological monitoring function acts as an “underwater health sentinel” for divers. On one hand, it dynamically captures potential risks—such as abnormal heart rate fluctuations indicating fatigue, or drops in blood oxygen signaling possible breathing equipment issues—enabling early risk detection and timely intervention. On the other hand, it provides surface command personnel with objective data for decision-making, reducing the chance of misjudgment that can arise from relying solely on subjective feedback. This fundamentally lowers safety hazards and establishes a robust safeguard for divers’ lives.

(1) Special Operations Diving

In closed-circuit rebreather (CCR) diving, the recycled breathing gas poses risks such as CO₂ retention and oxygen imbalance. The physiological monitoring system can track heart rate and blood oxygen in real time. For example, if the scrubber efficiency declines or gas mixture ratios become abnormal, causing a slight rise in CO₂ levels, early physiological responses such as increased heart rate may occur. The system can issue timely alerts to help divers adjust their breathing patterns.

During underwater infiltration or reconnaissance missions, divers often spend extended periods submerged. Long-duration static positions can lead to a gradual decline in blood oxygen saturation. The system continuously monitors and transmits divers’ physiological parameters, allowing command personnel to decide whether to adjust the mission or dispatch support, ensuring the safe execution of special operations.

(2) Public Safety Diving

In fire and rescue diving operations, divers often work in complex environments such as turbid waters or inside sunken vessels, where mental stress and physical exertion can cause physiological fluctuations. Real-time heart rate and blood oxygen feedback allows command personnel to intervene. For instance, if a rescuer’s heart rate remains above 130 bpm, personnel can advise “stop work to avoid overexertion.”

In training for police, SWAT, or rescue divers, high-intensity underwater exercises—such as weighted swims or tactical drills—can stress the body. By monitoring divers’ physiological data, the system can automatically issue alerts when indicators approach safety thresholds, helping instructors adjust training pace and prevent accidents. Post-training, the collected physiological data can be analyzed to assess workload for each exercise, providing a scientific basis for optimizing training plans and individualized programs.

(3) Scientific Research Diving

Scientific divers often conduct long-duration underwater tasks, where physiological status is affected by pressure and low temperatures. The physiological monitoring system provides real-time insight into their health.

For example, if a diver’s heart rate slightly drops due to low temperatures, the surface team can advise: “activate the suit’s heating system to maintain core body temperature.”

If blood oxygen slowly declines due to prolonged static posture, divers can be reminded to “move limbs appropriately to promote circulation,” ensuring that research tasks proceed smoothly while safeguarding personnel.

(4) Engineering Diving

Engineering divers performing high-intensity tasks such as underwater welding or maintenance may experience abnormal physiological indicators due to physical exertion or heavy equipment. The monitoring system provides real-time alerts.

For example:

If a diver’s heart rate rises during subsea pipeline welding, command personnel can instruct: “stop work.”

If blood oxygen gradually drops, equipment can be checked for insufficient oxygen supply, allowing timely troubleshooting and preventing physiological issues from affecting both project progress and diver safety.